Project Euler Problem #15

November 13, 2020

Intro

Problem #15 from Project Euler is a really interesting problem. Not only is there a clean mathematical solution to the question, but there are a bunch of non-optimal (or even downright ugly) but intuitive ways to solve the problem.

The easy way

The easiest, and probably fastest, way to solve this problem is to just use math. Consider the rules of the problem:

- Each path is composed of 2N steps that lead from the top left to the bottom right of the domain.

- Each step can only be a rightward or downward move.

- Because of the start and end positions, each path must have an equal number of down and right moves.

Based on these rules, you can build a valid path by starting with an empty list of 2N steps, selecting N steps to place a rightward move, and filling the remaining steps with downward moves. This is a Combination Problem! The number of valid paths you can possibly construct is 2N choose N.

A fun way

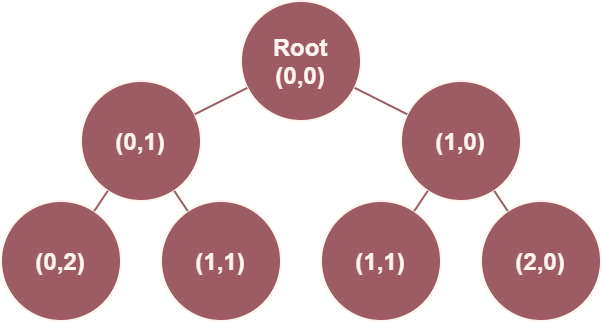

a tree

Maybe you’re itching for a reason to think about binary trees. You can look at every step in a path as a node in a binary tree. The starting position is the root node. The root node has two child nodes, one for a downward move and one for a rightward move. Each of those nodes have their own children in the same pattern. This means that two of the “grandchild” nodes actually describe different paths to the same point. In the above picture, downward moves are to the left and rightward to the right.

Using this tree, we can describe any path on an infinite grid. To constrain the grid (and know when we’ve reached the end point), we need to add some state to each node: an x and y position: (x,y). To create a new downward node in our domain, y must be less than N - the new node’s y value will be increased by 1. To create a new rightward node, x must be less than N - we’ll increase the node’s x. If a new node has state x == N and y == N, we’ve hit the end point of the grid!

If we actually build out this tree to full 2N depth, we’ll eat up a ton of memory. Conveniently, we don’t actually need to hold all of this state since we’re only interested in how many nodes in the tree are at the end point. We can just pretend to build the tree with a recursive function. Here’s an implementation in Rust🦀:

// The size of our domain in steps

// The grid is NxN steps

// Really, our position grid is N+1xN+1

// [0,0] describes the start and [N,N] describes the end point

static N:u32 = 20;

fn build_node(x:u32, y:u32, n_ends:&mut u64) {

// If x==y==N, we're at the end point!

if x == N && y == N {

*n_ends += 1;

return;

}

// Recurse for each child node if possible

if x < N {

build_node(x + 1, y, n_ends);

}

if y < N {

build_node(x, y + 1, n_ends);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut n_ends:u64 = 0;

// This describes the root node

build_node(0, 0, &mut n_ends);

println!("Total unique paths: {}", n_ends);

}

Go get a coffee or two, because this took ~30min to run on my machine.

Edit: This can be heavily optimized without abandoning the tree structure! More info in this more recent post.

An ugly way

Suppose you were told to solve this problem on an FPGA and you have no clue what combination is. Since we know the length of a path is 2N, we’ll start with a 2N-bit wide counter. Let’s say down = 1 and right = 0. We can initialize a down-counter with all 1s and let it run all the way down to 0. Since we know a valid path has #rights=#downs=N, we’ll look at every counter value and keep track of the number of values which have exactly N ones. That number is the number of possible paths!

We can even slightly optimize this by recognizing that we only have to evalute all of the paths that start with a downward move and multiply the result by two. This follows from our tree representation above. Rust example below:

// The size of our domain in steps

static N:u32 = 20;

fn main() {

let n_ends:u64 = (2u64.pow(2*N-1)..2u64.pow(2*N)).map(|x| (x.count_ones()==N) as u64).sum();

println!("Total unique paths: {}", 2*n_ends);

}

Go get another coffee. This took ~15 minutes on my machine. In the end, the mathematical solution is the way to go, but it’s still fun to explore other solutions.